HPV Vaccine Protects for Over 12 Years

Scotland’s HPV vaccination program continues to protect women from cervical precancer over 12 years later.

When a national vaccine program begins, the real question is how long the protection lasts. In Scotland, the answer now spans more than a decade for the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination.

A team of researchers in Scotland analyzed linked data from their national immunization and cervical screening programs and found that women vaccinated against HPV at age 12–13 years retained high protection against serious cervical precancerous lesions.

Understanding long-term HPV vaccination protection

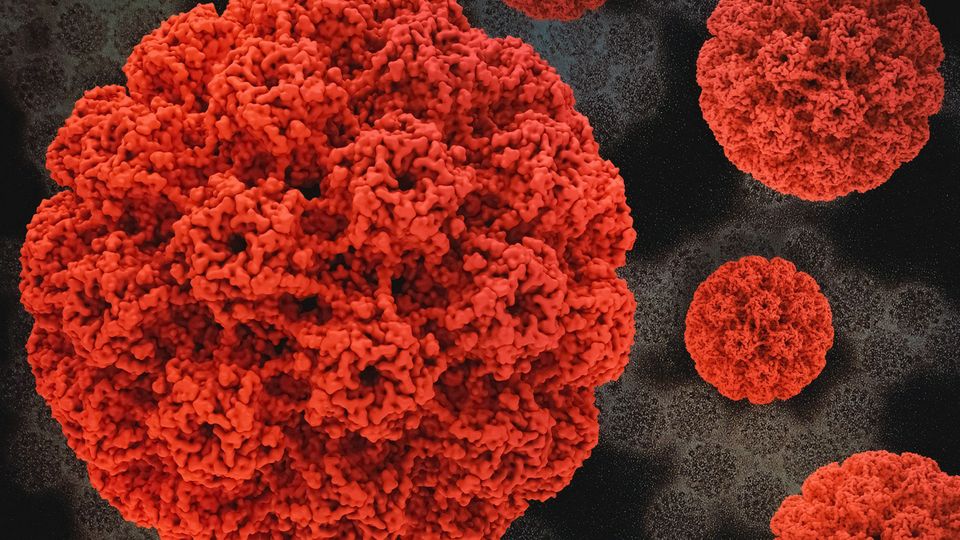

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women globally, with around 660,000 new cases and an estimated 350,000 deaths reported in 2022. Most of these cases are caused by persistent infection with high-risk types of HPV, which is spread through sexual contact.

Vaccination against HPV has been shown in trials to block infection and early pre-cancerous changes in the cervix. Yet, few studies have followed large vaccine-treated populations for more than a decade.

In Scotland, girls aged 12–13 years have been offered the bivalent HPV vaccine since 2008, with a catch-up option up to age 18 years.

Bivalent HPV vaccine

A vaccine that protects against two HPV types, specifically HPV 16 and 18, which cause most cervical cancers.

Previous work in the region confirmed a sharp drop in HPV prevalence and early lesions among vaccinated teens, but key questions remained: How long does protection last? Do older girls or those with fewer doses gain the same benefit? And do vaccinated cohorts also protect others through herd effects?

The new study aimed to investigate how effective the vaccine remains at preventing high-grade cervical lesions across 2 screening rounds, more than 12 years after vaccination.

Long-term HPV vaccination outcomes

The team analyzed data from Scotland’s national cervical screening database to assess how well the HPV vaccine continues to protect women more than a decade after it was introduced. The researchers examined records from 271,896 women born between 1988 and 1996 who had attended at least 1 cervical screening.

Women were grouped by vaccination status: complete (three doses or two given at least five months apart), incomplete (one dose or two given less than five months apart) and unvaccinated. The researchers compared the rates of high-grade cervical changes, including CIN2+ and CIN3+, in these groups up to August 2020, ~12 years after vaccination. High-grade lesions such as CIN2+ and CIN3+ are recognized precursors to invasive cervical cancer, making them important endpoints in vaccine studies.

CIN2+ and CIN3+

CIN2+ refers to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse, which includes CIN2, CIN3 and cervical cancer. CIN3+ refers to CIN3 or worse, which includes CIN3 and cervical cancer.

Protection remained high in vaccinated individuals. Among those inoculated at age 12–13 years, vaccine effectiveness was 72.6% for CIN2+ and 81.7% for CIN3+, with only a small decline in older age groups.

“There has been no reduction in protection over the 12 years since the vaccine was introduced,” first author Dr. Timothy Palmer, an honorary senior lecturer at the Centre for Reproductive Health at the University of Edinburgh, told Technology Networks.

However, vaccination after age 18 years offered no measurable benefit.

“Vaccine efficacy quite clearly declines with older age at vaccination,” he explained. “The vaccine prevents new infections but does not treat persistent infections.”

“HPV infection is almost inevitable in sexually active women, and the longer a woman has been sexually active, the greater the number of different HPV types she is likely to encounter,” Palmer added.

The study also detected strong herd protection in the cohort. Even unvaccinated women showed lower rates of disease as HPV transmission fell across the population.

“The very high uptake rates of vaccination mean that there are too few individuals carrying vaccine-targeted HPV types for continued transmission,” Palmer said. “The overall reduction in the vaccine-protected types in the younger population means there is less chance of non-immunized individuals coming into contact with these HPV types.”

Protection was particularly strong among women in the most deprived areas, helping to narrow long-standing health inequalities.

Implications of HPV vaccination: screening, limitations and next steps

The findings leave little doubt that Scotland’s HPV vaccination program is working. After more than a decade of real-world follow-up, the data show that the bivalent HPV vaccine continues to protect young women from the early changes that can lead to cervical cancer. It’s strong evidence that vaccinating girls before they become sexually active provides lasting protection, which is what global health agencies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the UK’s Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation have been advocating.

Fewer cases of HPV infection also mean fewer chances for the virus to spread, which gives a measure of protection to unvaccinated women, too. That community effect could help make cervical cancer an increasingly rare disease.

However, the vaccine isn’t a complete shield.

“There are more HPV types that can cause the precursors of cancer, and hence invasive disease, than are covered by the bivalent or any other HPV vaccine. Screening is the only way to detect these cases,” said Palmer.

As the vaccine-targeted HPV types fade out, a greater share of remaining cases will come from the less aggressive, non-vaccine types.

“We do not know how the non-vaccine-protected types will behave,” Palmer said, “but they are known to be less aggressive, so screening intervals can probably be longer than the current five years after a negative test.”

“Vaccination is an essential component of the WHO strategy for eliminating cervical cancer as a public health problem,” said Palmer. “However, as vaccination has little effectiveness if given over the age of 18 in our study, it cannot be the only route to elimination. For unvaccinated women, screening is the only way to prevent the development of invasive cancer.”

For now, the message is straightforward: early vaccination works and the protection lasts. But, as Palmer emphasized, “it is important to maintain the high vaccine uptake in school-aged girls and boys to continue the progress made as a result of vaccination.”

Reference: Palmer TJ, Kavanagh K, Cuschieri K, et al. Sustained impact of bivalent HPV immunisation on CIN incidence over two rounds of cervical screening. Intl J Cancer. 2025:ijc.70183. doi: 10.1002/ijc.70183

About the interviewee:

Dr. Timothy Palmer is the Scottish Clinical Lead for cervical screening. Palmer plays an important role in the direction of development of cervical cytology services in Scotland and in managing the changes that this involves. His position as an honorary senior lecturer in the Division of Pathology provides an academic base for being involved with research and development taking place in the field of HPV (human papillomavirus) that is of particular relevance to the development of cervical screening services.